Sleep patterns change with age, and these changes are independent of other factors such as medical conditions and medication. Age-related changes in sleep include advanced sleep timing, shortened nocturnal sleep duration, increased frequency of daytime naps, increased number of nocturnal awakenings and time spent awake during the night, and decreased slow-wave sleep.

The total sleep time (TST) decreases with age, but this decline is not consistent after entering older age brackets. Older adults also experience a slight increase in sleep latency, or the time it takes to fall asleep. The number of arousals and total time awake after falling asleep also increases with age.

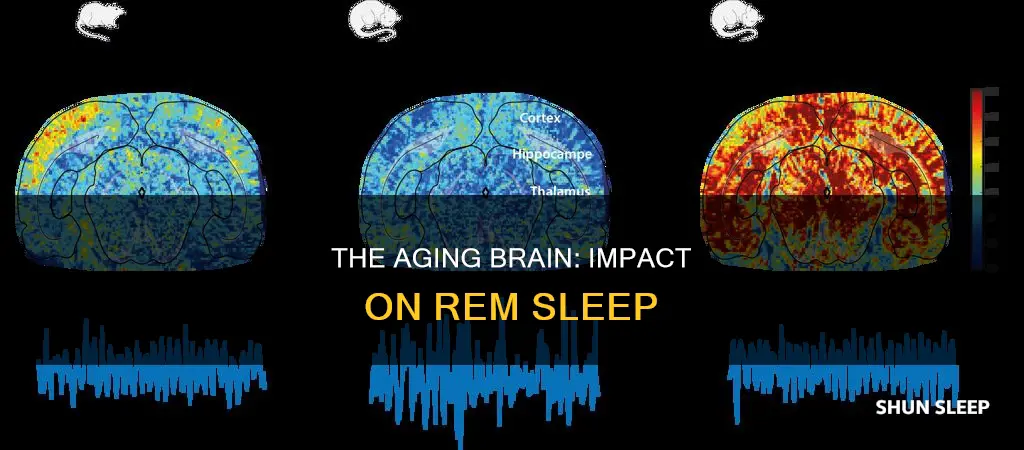

Older adults spend a lower percentage of their sleep time in both slow-wave sleep (deep sleep) and REM sleep compared to younger adults. The circadian rhythm amplitude is also dampened in older adults, and the circadian rhythm begins to progressively advance, with older adults becoming sleepy earlier in the evening and waking earlier in the morning.

REM sleep is often associated with dreaming and is thought to assist in brain development, especially early in life. Newborns and infants spend about twice as much time as adults in REM sleep.

What You'll Learn

Total sleep time decreases with age

As we age, the amount of time we spend sleeping decreases. This is a well-documented phenomenon that has been observed across numerous studies. The current literature supports the idea that total sleep time (TST) decreases with age.

Age-Related Changes in Sleep

Several physiological alterations occur with normal ageing, and sleep patterns change with advancing age, independent of other factors such as medical conditions and medications. Age-related changes in sleep include advanced sleep timing, shortened nocturnal sleep duration, increased frequency of daytime naps, increased awakenings during the night, and decreased slow-wave sleep.

Total Sleep Time Decreases

Sleep Efficiency

Sleep efficiency, or the ability to fall and stay asleep, remains largely unchanged from childhood to adolescence, but it significantly decreases with age in adulthood. Unlike other sleep parameters that stabilise after the age of 60, sleep efficiency continues to decline slowly with advancing age.

Sleep in Older Adults

Older adults tend to have shorter nocturnal sleep durations and spend less time in deep sleep (slow-wave sleep). They also experience more frequent awakenings during the night and have an increased number of daytime naps. These changes in sleep patterns are associated with alterations in the circadian and homeostatic processes, as well as normal physiological and psychosocial changes that occur with ageing.

Sleep and Age-Related Changes

The relationship between sleep and age is complex, and while total sleep time decreases with age, other factors come into play. The circadian system and sleep homeostatic mechanisms become less robust with normal ageing, contributing to changes in sleep patterns. Additionally, the amount and pattern of sleep-related hormone secretion change with age.

Sleep Disorders

It is important to note that while age-related changes in sleep are expected, sleep disorders are also common in older adults and can contribute to overall higher rates of poor sleep. Sleep-disordered breathing, insomnia, circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, and parasomnias are frequently observed in older adults.

In summary, total sleep time decreases with age, and this decrease is more pronounced when comparing young adults with middle-aged or older adults. However, after the age of 60, TST tends to plateau, and other sleep parameters remain relatively stable. Age-related changes in sleep are influenced by alterations in the circadian and homeostatic processes, as well as physiological and psychosocial changes.

Enhancing REM Sleep: Simple Strategies for Deeper Rest

You may want to see also

Sleep efficiency continues to decline with age

Sleep efficiency is a measure of the quality of sleep, and it continues to decline with age. Sleep efficiency is calculated by dividing the total sleep time by the time spent in bed. As people age, they experience a decrease in total sleep time, which is the amount of time spent sleeping at night or during the day. This decrease in total sleep time is accompanied by an increase in the number of awakenings and time spent awake during the night. As a result, older adults may take more time to fall asleep and experience more fragmented sleep. These changes in sleep patterns can be attributed to various factors, such as physiological changes, hormonal changes, and alterations in the circadian rhythm.

The decline in sleep efficiency with age is influenced by several factors. One factor is the decrease in slow-wave sleep or deep sleep. Slow-wave sleep is essential for restoring the body and consolidating memories. As people age, they spend less time in slow-wave sleep, which can impact their ability to feel rested and may contribute to cognitive decline. Additionally, the circadian rhythm becomes less robust with age, leading to an advanced sleep schedule. Older adults tend to feel sleepy earlier in the evening and wake up earlier in the morning. This shift in the sleep-wake cycle is associated with changes in the timing of melatonin and cortisol secretion, which are hormones that regulate sleep and wakefulness.

The decrease in sleep efficiency is also related to changes in sleep architecture. Sleep architecture refers to the different stages of sleep, including non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. With age, there is a decrease in the percentage of N3 or slow-wave sleep and an increase in the percentage of N1 and N2 sleep. N1 is the lightest stage of sleep, while N3 is the deepest stage. This shift in sleep architecture may contribute to the fragmented sleep patterns observed in older adults.

Furthermore, the prevalence of sleep disorders, such as sleep-disordered breathing and insomnia, increases with age. Sleep-disordered breathing includes conditions like obstructive sleep apnea, where breathing is interrupted during sleep. Insomnia, on the other hand, is characterized by difficulty falling or staying asleep. These sleep disorders can further contribute to the decline in sleep efficiency and overall sleep quality in older adults.

In summary, sleep efficiency continues to decline with age due to a combination of factors, including changes in sleep architecture, hormonal changes, alterations in the circadian rhythm, and the increased prevalence of sleep disorders. These changes in sleep patterns can have significant implications for the health and well-being of older adults, highlighting the importance of addressing sleep issues in this population.

Exploring Age's Impact on REM Sleep Patterns

You may want to see also

Sleep architecture changes with age

Older adults spend a lower percentage of their sleep time in both slow-wave (deep) sleep and REM sleep compared to younger adults. The time it takes to fall asleep increases slightly as well. The number of arousals and total time awake after falling asleep also increases with age. Older adults do not experience increased difficulty in their ability to return to sleep following arousals compared to younger adults. Additionally, older adults spend more time napping during the day.

Melatonin secretion is reduced, and the circadian rhythm amplitude is dampened in older adults. After around age 20, the circadian rhythm begins progressively advancing (i.e., shifting earlier), with older adults becoming sleepy earlier in the evening and waking earlier in the morning.

The changes in sleep architecture and the circadian rhythm become less robust with normal aging. The amount and pattern of sleep-related hormone secretion change in normal aging. All these changes contribute to or correlate with age-related changes in sleep.

Beta Waves During REM Sleep: What Does It Mean?

You may want to see also

Circadian rhythms become less robust with age

Circadian rhythms, which regulate several physiological functions, including body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, hormone release, bone remodelling, sleep-wake rhythm, and rest-activity patterns, become less robust with age. This weakening of the circadian system typically presents as an advance in circadian timing, a decrease in circadian amplitude, and a reduced ability to adjust to phase shifting.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is the central endogenous circadian pacemaker that regulates 24-hour circadian rhythms. The disruption of circadian rhythms with advancing age may be associated with a progressive decline in the function of the SCN. The timing and structure of sleep are mainly regulated by the circadian system and homeostatic sleep regulation. Older adults commonly experience an advance of sleep schedule to earlier hours. They tend to feel sleepy earlier in the evening and wake up earlier in the morning than desired. This earlier sleep timing in older adults may be due to the age-related phase advance in their circadian rhythm. This phase advance is seen not only in the sleep-wake cycle but also in the body temperature rhythm and in the timing of the secretion of melatonin and cortisol.

The reduced amplitude of daytime activity may result in daytime napping, which may further reduce the amplitude of the sleep-wake rhythm. Age-related decline in amplitude of melatonin secretion may also play a role in sleep problems in older adults. The ability to phase-shift decreases with age. Older adults are subject to more difficulties in adjusting to phase shifts, such as shift work and jet lag. The age-related loss of rhythmic function within the SCN may partially explain this impaired ability in phase shifting.

The Dark Side of REM Sleep Deprivation

You may want to see also

Sleep-related hormone secretion changes with age

Growth hormone (GH)

The secretion of growth hormone (GH) and slow-wave sleep influence each other. GH secretion pulses during nocturnal sleep, about an hour after sleep onset, and decreases during transient awakenings. There is an age-related decline in GH secretion, which peaks during adolescence and declines exponentially between young adulthood and middle age. This decline is similar to the detected age-related decrease of slow-wave sleep. The decline in nocturnal GH with aging may impact slow-wave sleep and may be partially responsible for the observed reduction of slow-wave sleep in aging.

Cortisol

Cortisol secretion has a clear circadian pattern, with a peak shortly after morning awakening and a nadir in the late evening. Sleep, particularly slow-wave sleep, inhibits cortisol secretion. The rise of cortisol secretion during sleep could lead to awakenings. The circadian rhythm of cortisol changes with aging, with a decreased circadian amplitude, an elevated nocturnal cortisol level, and a likely phase-advanced rhythm. The elevated nocturnal cortisol level may contribute to decreased slow-wave sleep and frequent awakenings during nocturnal sleep in older adults.

Prolactin

There is no clear evidence that prolactin secretion affects sleep. However, sleep onset is associated with increased prolactin secretion, regardless of whether it is day or night sleep. Decreased slow-wave sleep or fragmented sleep may be associated with a reduced elevation of prolactin during nocturnal sleep. Studies suggest that nocturnal prolactin in healthy older adults is significantly lower than in young adults.

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

TSH secretion has a circadian pattern, with a stable low level during the daytime, a peak around sleep onset, and a gradual decline through the night. Slow-wave sleep is associated with inhibited nocturnal TSH secretion, and awakenings are associated with increased nocturnal TSH secretion. The circadian release of TSH is maintained with aging. However, research suggests that the overall 24-hour TSH secretion is decreased in older adults.

Melatonin

The 24-hour profile of plasma melatonin is primarily regulated by the light-dark cycle and the sleep-wake cycle. Melatonin secretion decreases with aging, but daytime melatonin may remain unchanged. The elevation of nocturnal melatonin in older adults is significantly reduced compared to young adults. Studies suggest that the age-related decline in melatonin secretion contributes to increased sleep disruption in older adults.

Gonadotropins and sex steroids

Changes in gonadotropins and sex steroids with aging are associated with sleep changes in older adults. In men, testosterone levels progressively decrease after 30 years of age, and older men may lose the diurnal testosterone pattern. The decreased testosterone with aging may relate to the increased sleep fragmentation in older adults. In women, estradiol levels decrease, and follicle-stimulating hormone levels increase significantly during menopause. These changes in reproductive hormones have been associated with increased complaints of difficulty falling and staying asleep. The decreased levels of endogenous estrogen and progesterone may negatively impact the upper airway, increasing the incidence of sleep-disordered breathing after menopause.

Understanding Deep Sleep: Is REM Sleep Deep Sleep?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

REM sleep is the stage of sleep where most dreams happen. Its name comes from how your eyes move behind your eyelids while you’re dreaming. During REM sleep, your brain activity looks very similar to brain activity while you’re awake.

The percentage of REM sleep decreases with age. The decline is small, but significant. The rate of decline is estimated to be around 0.6% per decade.

Slow-wave sleep is another name for deep sleep. It is the deepest stage of NREM sleep. Your body takes advantage of this very deep sleep stage to repair injuries and reinforce your immune system.

The percentage of slow-wave sleep decreases with age. The older you get, the less you need.

Total sleep time decreases with age. The number of hours of sleep that are good for your health can also change during your lifetime.

The number of sleep cycles per night decreases with age. Most people go through four or five cycles per night (assuming they get a full eight hours of sleep).